A Maternal Healthcare Crisis

By: Abby Gemechu

Though medical care has undoubtedly improved over the last few decades, there is no question that still existing economic, social, and racial disparities in healthcare not only cause thousands of preventable deaths each year, but continue to enforce and exacerbate systemic inequity.

The medical discrimination and biases Black women face in particular, both as patients and caregivers, in healthcare facilities is one of such issue.

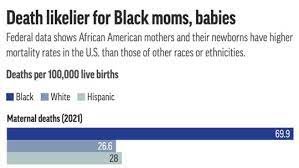

While Black women are statistically more likely to experience complications during the length of their pregnancy and throughout labor and childbirth, they do not receive the adequate care. Nationwide, Black women are three times more likely to die in labor than their white counterparts, with the statistics mostly consistent across economic and social status. In Cleveland alone, the maternal death rate for Black women is nearly twice as much as the fatality rates of white and Hispanic women, clocking in at "29.5 maternal deaths per 100,000 Black mothers.”

Furthermore, maternal healthcare deserts, areas that lack facilities that offer obstetrics or gynecology care, make it even more difficult for Black women in rural towns especially to access the treatment they need and deserve. According to Rachel Treisman of NPR, this issue disproportionately harms mothers of color, as “one in 4 Native American babies and 1 in 6 Black babies,” are born in these deserts each year.

Though maternal healthcare disparities can be attributed to a number of racial, economic, and social factors, a notable contributor is caregivers’ unconscious bias in the examining room. Physicians often tend to disregard their Black patients’ complaints, concerns, and questions, with patient reports of neglect and dismissal when informing their doctors of pain and suffering.

The way in which Black women are perceived by medical experts compared to our counterparts (doctors, nurses, specialists, etc.) when seeking for medical advice or assistance has a myriad of grave consequences, such as the aforementioned maternal death rate, make it exponentially more difficult for us to receive the care and treatment we deserve, especially when it is a matter of life or death. As a result, viewing systematic issues of injustice, like this one, through the lens of intersectionality is crucial, given that it better allows us to determine the factors exacerbating said issues. Without the consideration of intersectional ideas in solution-brainstorming and decision-making, the experiences of people who hold multiple marginalized identities are erased, further contributing to the discrimination that Black women face in the medical field.

Sources:

https://www.cdc.gov/healthequity/features/maternal-mortality/index.html

https://nationalpartnership.org/report/black-womens-maternal-health/

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/11/nyregion/birth-centers-new-jersey.html

https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2019/p0905-racial-ethnic-disparities-pregnancy-deaths.html